This report outlines the context of the seven instances of rate cuts in the United States from 1982 to 2019, as well as the economic and major asset performance before and after the rate cuts, and discusses the implications of historical experience for the present.

1.

Context of the rate cut initiation.

Each time the Federal Reserve initiated rate cuts, there was a certain commonality, with signs of economic and/or inflation slowdowns; there were also unique contexts: 1) 1984-1986, high deficits and strong dollar.

2) 1989-1992, savings and loan crisis.

3) 1995-1996, no economic shock.

4) 1998, Asian financial crisis.

5) 2001-2003, internet crisis.

6) 2007-2008, subprime mortgage crisis.

7) 2019, trade tensions.

2.

Economy after rate cuts.

In the seven rounds of rate cut cycles, the U.S. economy experienced a "hard landing" three times and achieved a "soft landing" four times.

In terms of production and consumption, after the first rate cut, the U.S. ISM manufacturing PMI and private real consumption growth rate usually continue to weaken for three months and bottom out and rebound within three to six months.

In terms of employment, after the first rate cut, the trend of the U.S. unemployment rate is uncertain, but the "Sum Index" usually rises within six months after the rate cut, indicating that the marginal pressure on the job market continues to increase.

In terms of inflation, after the first rate cut, the trend of the U.S. PCE and core PCE inflation rates is uncertain, but the model's 10-year inflation expectations usually decline within three to six months, which may imply that the Fed's rate cuts themselves are not easy to trigger inflation and inflation expectations rebound, and the possible reason is that the economic slowdown has a strong drag on inflation and inflation expectations.

3.

Assets after rate cuts.

Before the first rate cut, U.S. Treasury bonds, gold, etc., usually benefit; after the first rate cut, the risk of price volatility for most assets actually increases, and two to three months later, U.S. Treasury bonds and stocks may perform positively.

Before and after the rate cuts, the winning rate of U.S. Treasury bonds is relatively high.

1) The trend of U.S. Treasury bond rates is downward, but in the case of a "soft landing," it may rebound within one to two months after the first rate cut.

2) The trend of the U.S. dollar index is not absolutely related to rate cuts and whether it is a "soft landing."

3) The rise of the stock market may "stall" before and after the first rate cut, but it usually resumes rising two to three months after the rate cut.

4) The probability of gold rising before the rate cut is relatively large, but the trend after the rate cut is unclear.

5) The probability of oil prices falling after the rate cut is relatively large, but it is not absolute.

4.

Implications for the present.

First, based on the economic performance before the rate cut, it is difficult to judge whether the U.S. economy can achieve a "soft landing" afterwards.

Second, if there is no serious economic or financial market shock in the future, it is more likely that this round of rate cut cycles will achieve a "soft landing."

Third, this round of the Fed's rate cuts started relatively late, and the signals of economic and job market weakness before the rate cut were strong.

After the rate cut, the economy and job market may also continue to decline for a period of time.

The trend of this round of assets needs to be judged comprehensively in combination with the experience of the rate cut cycle, as well as the macro background of the U.S. election, Japan's rate hike, etc.

Specifically: 1) The 10-year U.S. Treasury bond rate may rebound within one to two months after the first rate cut, and then continue to decline.

2) The U.S. dollar index may not fall due to rate cuts, but it may be dragged down by the appreciation of the yen.

3) The adjustment risk of the stock market before and after the first rate cut is not small, but the overall direction is still positive.

4) Gold has risen a lot before the rate cut, and it is more likely to consolidate after the rate cut.

5) The price of oil is more likely to remain volatile after the rate cut.

Risk warning: The statistical sample is limited, the U.S. economy and employment may decline unexpectedly, U.S. inflation may rebound unexpectedly.

Unexpected fluctuations in the international financial market, unexpected international geopolitical situations, etc.

This report reviews the seven rounds of rate cut cycles in the United States from 1982 to 2019, focusing on the context of the Fed's rate cuts, as well as the economic and major asset performance before and after the rate cuts, and discusses the implications of historical experience for the present.

Before each rate cut, the Fed has shown signs of slowing economic and/or inflation.

Looking back, in the seven cycles, the U.S. economy experienced a "hard landing" three times and achieved a "soft landing" four times.

Within a few months after the first rate cut, the U.S. economy and employment may continue to weaken, and inflation is not easy to rebound.

Before the first rate cut, U.S. Treasury bonds, gold, etc., usually benefit; after the first rate cut, the risk of price volatility for most assets actually increases, and two to three months later, the financial conditions relaxed by the rate cut and the expectation of recovery may make U.S. Treasury bonds and stocks perform positively.

Before and after the rate cuts, the winning rate of U.S. Treasury bonds is relatively high.

Looking back at the present, we believe that on the one hand, if there is no serious economic or financial market shock in the future, this round of rate cut cycles is more likely to achieve a "soft landing."

On the other hand, this round of the Fed's rate cuts started relatively late, and the signals of economic and job market weakness before the rate cut were strong.

After the rate cut, the economy and job market may also continue to decline for a period of time.

The trend of this round of assets needs to be judged comprehensively in combination with the experience of the rate cut cycle, as well as the macro background of the U.S. election, Japan's rate hike, etc.

01 Context of rate cut initiation.

This article focuses on analyzing the seven rounds of rate cut cycles in the United States from 1982 to 2019.

In our report "Rethinking the Great Stagnation in the United States," we studied the U.S. economy, policy, and asset performance from the 1970s to the 1980s.

After 1982, the Fed gradually began to shift to the "federal funds target procedure."

Before that, the Fed's policy objectives were relatively complex and diverse, using a comprehensive set of indicators such as the money supply (M1), discount rate, and federal funds rate.

This means that after 1982, the interest rate cycle divided by the federal funds target rate can relatively accurately reflect the real "monetary cycle."

The seven rounds of rate cut cycles we selected all start with the first rate cut after the rate hike (excluding the situation of rate cuts after a pause).

The rate cut cycle that started in 2019 intentionally excludes the rate cuts triggered by the pandemic in 2020, as much as possible to ensure that the selected rate cut cycles have "endogeneity," which has a strong enlightening significance for the present.

Overall, each time the Fed started rate cuts, there was a certain commonality, with signs of economic and/or inflation slowdowns; there were also unique contexts: 1) 1984-1986: high deficits and strong dollar.

From September 1984 to August 1986, the Fed maintained a rate cut trend for nearly two years, with a total rate cut of 562.5BP, and the upper limit of the federal funds target rate was reduced from 11.5% to 5.875%.

This round of rate cut cycle is not entirely coherent, and the Fed has raised rates slightly several times from January to March, July to August 1985, and April to June 1986.

According to an article by the New York Fed [1], the background of the Fed's first rate cut in 1984 was that the U.S. economy showed signs of slowing down after rapid growth at the beginning of the year, with the unemployment rate falling from 8% at the beginning of the year to 7.2% in June, and then rebounding to 7.5% in July and August.

At the same time, although the PCE inflation rate was still at the level of 3-4%, the decline rate was relatively fast, from 4.3% in March 1984 to 3.4% in September 1984, and inflation was no longer the main problem for the economy.

At that time, the Fed also faced two major economic "additional questions": one was the expansion of fiscal deficits under "Reaganomics."

After Reagan took office in 1981, he implemented supply-side reforms, increased government deficits and debt, to deal with the economic recession.

According to OECD and IMF data, from 1980 to 1983, the U.S. general government deficit rate increased by 2.8 percentage points to 7.2%, and the debt rate increased by 6.7 percentage points to 47.8%.

The second was the "strong dollar" and the expansion of the trade deficit.

From 1980 to 1984, the U.S. dollar index continued to strengthen, rising from around 85 to around 140 in August 1984, an increase of more than 60%.

During this period, the U.S. trade deficit expanded rapidly, from $16.2 billion in 1981 to $109.1 billion in 1984, an increase of 6.7 times.

2) 1989-1992: Savings and Loan Crisis.

From June 1989 to September 1992, the Fed started a rate cut cycle of more than three years, with a total rate cut of 681.25BP, and the policy rate upper limit was reduced from 9.8125% to 3%.

During this period, the Fed never raised rates, only paused rate cuts.

In 1989, the background of the Fed's rate cut was that the Fed's policy focus was on controlling inflation.

At the beginning of the year, Greenspan said in his speech to Congress that "the current inflation rate of 4%-5% is unacceptable."

However, the U.S. economy slowed down in the second quarter, including the cooling of non-farm data, the weakening of manufacturing PMI, and entering the contraction range, etc., and the PCE inflation rate also fell from 4.7% in February to 4.2%.

In 1990, U.S. inflation fluctuated, especially in August when the third oil crisis broke out, and the Fed slowed down the pace of rate cuts.

At the beginning of 1991, the United States intervened in the Gulf War, and with the decline in oil prices, the Fed continued to cut rates for a long time.

The larger background of this round of rate cuts was that from 1988 to 1991, the U.S. financial industry experienced the "savings and loan crisis," with more than 200 banking institutions (including savings and loan associations) going bankrupt or being rescued every year, which led to credit tightening and economic recession.

From August 1990 to March 1991, the U.S. economy fell into the recession period defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), lasting for 8 months.

(Refer to the report "Comparative Study of Two American 'Bank Crises': What Have We Learned from the Savings and Loan Crisis?

").Here is the translation of the provided text into English: 3.

1995-1996: "Soft Landing" Paradigm From July 1995 to January 1996, the Federal Reserve initiated a half-year interest rate reduction cycle, with a total of three cuts amounting to 75 basis points (BP), bringing the upper limit of the policy rate down from 6% to 5.25%.

Subsequently, the Fed maintained interest rates unchanged for over a year until it raised rates again in March 1997.

In 1995, the context for the Fed's rate cut was a slowdown in U.S. economic growth, with the real GDP growth rate on an annualized quarter-over-quarter basis only recording 1.2-1.4% in the first half of the year, below the average level of over 4% in 1994; the unemployment rate briefly rose from 5.4% to 5.8% in April and then fell back to 5.6-5.7%, the manufacturing PMI fell into the contraction range in May-June; the PCE inflation rate remained at 2.1-2.3% in the first half of the year.

An article by the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond pointed out that the Fed's decision to cut rates in 1995 was not "imminent," as there was no significant economic recession or substantial increase in the unemployment rate.

Therefore, this interest rate cycle is also seen as a typical case of a "soft landing."

On the other hand, the Fed's operations successfully avoided inflation from "taking off," with the PCE inflation rate hardly exceeding 2.3% during the rate reduction process, maintaining relative stability.

4.

1998: Asian Financial Crisis From September to November 1998, the Federal Reserve cut rates three times, totaling 75 BP, with the upper limit of the policy rate falling from 5.5% to 4.75%.

Prior to the rate cuts, the policy rate had been maintained at the 5.5% level for over a year and a half.

In 1998, the context for the Fed's rate cuts was that the economy maintained a certain resilience, but the external environment was turbulent, and the U.S. stock market experienced adjustments.

The U.S. real GDP growth rate on an annualized quarter-over-quarter basis remained at a relatively high level of 3.8-4.1% in the first half of the year, and the unemployment rate remained at a relatively low level of around 4.5% in the second half of 1998.

However, the manufacturing PMI fell into the contraction range in June; the PCE inflation rate had been slowly declining from 2% since 1997 and fell below 1% after February 1998.

In the second half of 1997, Thailand's abandonment of the fixed exchange rate triggered the "Asian Financial Crisis," and the Asian foreign exchange and financial markets continued to be turbulent in 1998.

In September 1998, the Russian financial market was also affected, and the crisis did not basically end until 1999.

From July to August 1998, the S&P 500 index experienced an adjustment of nearly two months, with the deepest drop approaching 20%.

The Federal Reserve's September 1998 meeting statement stated, "The rate cut was to mitigate the negative impact of the increasingly weak foreign economies and the insufficiently loose domestic financial environment on the U.S. economic outlook."

According to CNN's report on the day of the rate cut, the global market had high expectations for the Fed's rate cut; after the rate cut, the U.S. stock market fell as some investors believed the Fed's rate cut was too conservative.

However, in retrospect, the U.S. economy was not significantly impacted, with the real GDP growth rate on an annualized quarter-over-quarter basis reaching 5.1-6.6% in the second half of 1998.

The Fed revised its economic outlook upwards in March 1999 and resumed rate hikes in June.

Federal Reserve officials later stated that the rate cuts in 1998 were an overreaction, failing to realize how strong the U.S. economy was.

Despite this, then-Fed Chairman Greenspan did not regret the rate cuts and believed that the economic risks were more threatening than inflation risks at the time.

5.

2001-2003: Internet Crisis From January 2001 to June 2003, the Federal Reserve cumulatively cut rates 13 times, totaling 550 BP, with the upper limit of the policy rate falling from 6.5% to 1.0%.

The Fed's rate cut pace in this round was relatively fast, with the first rate cut of 50 BP, followed by five consecutive rate cuts of 50 BP, totaling 475 BP within a year.

The context for the Fed's rate cuts in 2001 was the bursting of the "internet bubble," turmoil in the financial markets, and signs of economic weakening.

At the end of the 1990s, the rapid development and popularization of internet technology represented by "Web1.0" led to an "entrepreneurial boom" and excessive speculation.

From October 1999 to March 2000, the NASDAQ index rose by up to 88% in five months, and the S&P 500 index rose by 11%.

From June 1999 to May 2000, the Federal Reserve cumulatively raised rates six times, totaling 275 BP, to counter economic overheating.

In March 2000, after reaching its peak, the NASDAQ index fell rapidly, and the internet stock bubble gradually burst.

As of January 2, 2001 (the day before the rate cut), the NASDAQ index had fallen by 55% from its peak in March 2000, although the S&P 500 index fell by less than 10% during the same period.

In 2000, the U.S. unemployment rate remained around 4.0%, the manufacturing PMI entered the contraction range starting in August, and the PCE inflation rate fluctuated at a relatively high level of 2.2-2.7%.

On January 3, 2001, the Federal Reserve announced an emergency rate cut of 50 BP, stating that "the context for the rate cut was softening sales and production, declining consumer confidence, tense conditions in some financial markets, and high energy prices weakening household purchasing power," but also emphasized that "inflationary pressures remain controllable."

6.

2007-2008: Subprime Crisis From September 2007 to December 2008, the Federal Reserve cumulatively cut rates 10 times, totaling 500 BP, with the upper limit of the policy rate falling from 5.25% to 0.25%, that is, to "zero interest rate."

For the next seven years, the Fed did not raise rates and successively implemented three rounds of quantitative easing (QE) operations.

In 2007, the context for the Fed's rate cuts was the outbreak of the subprime crisis, which severely threatened the U.S. economic outlook.

In the second and third quarters of 2006, U.S. GDP growth had already significantly slowed down, with the quarter-over-quarter annualized rate falling from 5.5% in the first quarter to 0.6-1.0%, and the GDP year-over-year in the first quarter of 2007 fell from over 2% to 1.6%, and then rebounded.

Prior to the rate cuts in 2007, the U.S. unemployment rate remained at 4.4-4.7%, the manufacturing PMI basically maintained expansion; the PCE inflation rate basically remained at 2.1-2.6%, but fell to 1.9% in August, and the core PCE inflation rate fell from around 2.5% at the beginning of the year to around 2% in June-August.

In 2007, the U.S. subprime crisis gradually fermented, and the "blowout" of BNP Paribas in August had a significant impact, becoming a key turning point in the beginning of this crisis.

On August 17, the Federal Reserve announced a 50 BP cut in the discount rate to 5.75%, but did not cut the federal funds target rate; the market reacted positively, and the stock market rose, with most investors believing that "the situation is controllable"; the market expected the Fed to cut rates by 25 BP in September, with more aggressive expectations of three cuts of 25 BP each within the year, and some critics worried that rate cuts would fuel inflation.

On September 18, the Federal Reserve cut the federal funds target rate by 50 BP to 4.75%, stating that the development of financial markets had increased the uncertainty of the economic outlook, and tighter credit conditions could exacerbate the real estate adjustment, and today's action was aimed at preventing financial market chaos and promoting long-term moderate growth.

In addition, the statement also pointed out that some inflation risks still exist, and the Federal Reserve will pay close attention to this.

7.

2019: Tense Trade Situation From August to October 2019, the Federal Reserve cut rates three times, totaling 75 BP, with the upper limit of the policy rate falling from 2.5% to 1.75%.

Prior to this round of rate cuts, the Fed had maintained interest rates stable for nearly eight months.

In March 2020, the Fed continued to cut rates due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In 2019, the context for the Fed's rate cuts was a robust economy and job market, but inflation below 2%, and tense trade situations.

In the first half of 2019, the U.S. real GDP growth rate on an annualized quarter-over-quarter basis recorded 2.2-3.4%, the manufacturing PMI maintained expansion but showed a downward trend, and fell into the contraction range in August; the unemployment rate fell from 4% at the beginning of the year to 3.6% in May-June; the PCE inflation rate remained at 1.4-1.6%, and the core PCE inflation rate fell from around 1.9% at the beginning of the year to around 1.6% in March-May.

On July 31, 2019, the Federal Reserve announced a rate cut of 25 BP to 2.25%, stating that the U.S. economy was growing moderately, the job market was robust, but overall and core inflation rates were both below 2%, without particularly emphasizing the motivation for the rate cut.

The statement also showed that two members opposed the rate cut and supported keeping interest rates unchanged.

NPR reported that this rate cut was an "insurance policy" aimed at preventing economic slowdown, especially considering the tense trade situation and the background of slowing global growth; the market reacted negatively that day, and the stock market fell, as investors believed the Fed's motivation for the rate cut was not positive enough; then-President Trump also tweeted, "Powell has let us down."

On October 30, after the third rate cut, the Fed signaled a pause in rate cuts, partly because the trade situation improved, that is, positive progress was made in U.S.-China trade negotiations and Brexit negotiations.

02 The Economy After Rate Cuts 1.

"Hard Landing" and "Soft Landing" In the seven rate cut cycles since 1982, the U.S. economy has experienced three "hard landings" (1989-1992, 2001-2003, 2007-2008), that is, after the rate cuts, the U.S. economy fell into the recession range defined by the NBER, and the easing cycle (including other easing operations after the rate cuts) lasted for more than three years.

The other four times achieved a "soft landing" (1984-1986, 1995-1996, 1998, 2019), in these cycles, although the economy may have weakened temporarily, the extent and duration of the weakening were limited, and it was not defined as a recession range.

The rate cut cycle was as short as three months, and the longest did not exceed three years.How might the US economy, employment, and inflation develop before and after the first interest rate cut?

We primarily analyzed the changes in various US economic indicators during the 6-month period before and after the first interest rate cut in 7 cycles (see Appendices 1 and 2), and the following conclusions can be drawn: 1.

Production and Consumption: Weakness before and after the rate cut After the first rate cut, the US ISM Manufacturing PMI and private real consumption growth usually continue to weaken within 3 months, and then bottom out and rebound within 3-6 months.

In a "soft landing" scenario, real consumption typically shows greater resilience, but the manufacturing PMI may still weaken.

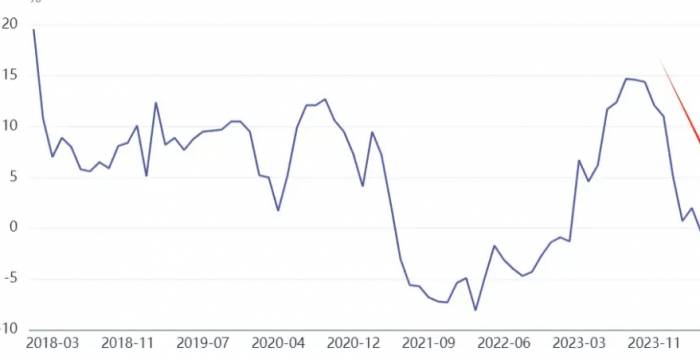

In the 7 cycles, the ISM Manufacturing PMI almost always showed a significant weakening 3-6 months before the rate cut, with an average decline of 6.2 percentage points from 6 months before the rate cut to the month of the first rate cut, and a high probability of falling into a contraction range.

After the first rate cut, there is still a high probability of further weakening within 3 months, with an average decline of 1.3 percentage points compared to the month of the first rate cut, but there is a high probability of rebounding within 6 months after the first rate cut, with the average decline narrowing to 0.6 percentage points compared to the month of the first rate cut.

The year-on-year growth rate of real personal consumption expenditure (PCE) shows a similar pattern, with an average decline of 0.3 percentage points from 6 months before the first rate cut to the month of the rate cut, and a further average decline of 0.5 percentage points within 3 months after the rate cut compared to the month of the rate cut, and the average decline narrowing to 0.3 percentage points within 6 months after the rate cut compared to the month of the rate cut.

In both "hard landing" and "soft landing" scenarios, the trend of manufacturing PMI showed weakness, with no significant difference; however, the change in the growth rate of real private consumption was quite different, with a clear downward trend in all 3 "hard landings" and a possible upward trend, or a rebound within a year after a phased decline in 4 "soft landings".

2.

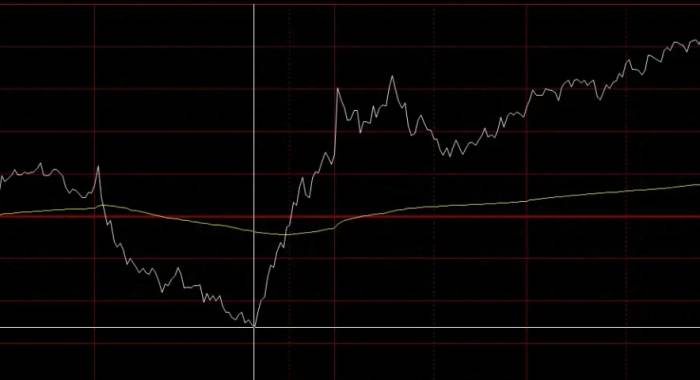

Employment: Pressure remains after the rate cut After the first rate cut, the trend of the US unemployment rate is uncertain, but the "Sahm Index" [9] (the difference between the 3-month moving average of the unemployment rate and the lowest point of the 3-month rolling moving average in the previous 12 months) usually rises within 6 months after the rate cut, suggesting that the marginal pressure on the job market continues to increase.

The unemployment rate is more likely to rise in a "hard landing" scenario, and may accelerate after 6 months of the first rate cut.

In the 7 cycles, the US unemployment rate is more likely to rise 1-2 months before the rate cut, but within 6 months after the first rate cut, the probability of the unemployment rate rising and falling is roughly equal.

However, the Sahm Index, which more accurately reflects the marginal changes in the job market, is likely to rise significantly one month before the rate cut, and is more likely to rise further within 6 months after the rate cut.

Specifically, compared to the month of the rate cut, the Sahm Index has risen by an average of 0.12 and 0.20 percentage points respectively after 3 and 6 months of the rate cut.

In both "hard landing" and "soft landing" scenarios, the unemployment rate is more likely to rise in a "hard landing" scenario, but usually rises relatively little within 6 months after the rate cut, and accelerates after 6 months.

In the two "hard landings" of 2001 and 2007, the "Sahm Index" rose to 0.5 within 6-7 months after the first rate cut, triggering the "Sahm Rule"; in other cases, it did not reach 0.5 within a year after the first rate cut.

3.

Inflation: Not easy to rebound after the rate cut After the first rate cut, the trend of the US PCE and core PCE inflation rates is uncertain, but the model's 10-year inflation expectation usually declines within 3-6 months, or implies that the Fed's rate cut itself is not easy to trigger an inflation and inflation expectation rebound, and the possible reason is that the economic weakness has a strong drag on inflation and inflation expectations.

In the 7 cycles, from 6 months before the first rate cut to the month of the rate cut, the PCE and core PCE year-on-year usually decline, with an average decline of 0.14 and 0.21 percentage points respectively.

However, after the first rate cut, the probability of the above inflation rates continuing to decline and rebounding is roughly equal, and the probability of the core PCE stabilizing is relatively large.

On the other hand, the Atlanta Fed's model's 10-year inflation expectation is likely to decline significantly before and after the rate cut, with an average decline of 0.27 percentage points from 3 months before the rate cut to the month of the rate cut, and an average decline of 0.13 and 0.11 percentage points respectively within 3 months and 6 months after the rate cut compared to the month of the rate cut.

In both "hard landing" and "soft landing" scenarios, there is no significant difference in the trend of core PCE, and both may show resilience; the trend of model inflation expectations also shows no significant difference, and there has been a certain degree of decline after the first rate cut.

In addition, the absolute level of inflation is not significantly related to whether it is a "soft landing" or not.

03 Asset development before and after the rate cut How do asset prices develop before and after the first rate cut?

We mainly analyzed the changes in the prices of major asset classes during the 60 days before and 90 days after the first rate cut in 7 cycles (see Appendix 3), and the following conclusions can be drawn: 1.

US Treasury bonds: Interest rates tend to decline The trend of US Treasury bond interest rates is downward, but in a "soft landing" scenario, they may rebound in the first 1-2 months after the first rate cut.

In the 7 cycles, from 2 months before the rate cut to 3 months after the rate cut, the 10-year US Treasury bond interest rate has generally maintained a downward trend.

After the first rate cut, the 10-year US Treasury bond interest rate usually still has room to decline, with an average decline of 20BP within 60 days after the rate cut based on the day before the first rate cut.

However, in the three "soft landings" of 1995, 1998, and 2019, the downward space for the 10-year US Treasury bond interest rate was relatively limited, and it may rebound in stages 1-2 months after the rate cut.

2.

US dollar: Direction unclear The trend of the US dollar index is not absolutely related to the rate cut and whether it is a "soft landing".

In the 7 cycles, the probability of the US dollar index rising and falling is basically equal within 1-3 months after the rate cut.

In the three "hard landings", the US dollar index is more likely to weaken in stages before and after the rate cut, but in two cases, it exceeded the level 2 months before the rate cut within 3 months after the rate cut.

In the four "soft landings", in three cases, the US dollar index was flat or rebounded before and after the rate cut.

A special case is 1998, when the Fed only cut rates three times and the US economy had a "soft landing", but the US dollar index weakened significantly before the rate cut, stabilized after the rate cut, but did not rebound to the level 2 months before the rate cut.

The special background at the time was the Asian financial crisis, which caused the US dollar index to rise significantly for most of 1997-1998, and began to fall rapidly in August 1998.

Although the Fed started to cut rates in September, the US dollar index was still in the inertia of falling.

3.

US stocks: Temporary halt in the rise The rise of US stocks may "stall" before and after the first rate cut, but usually resumes rising 2-3 months after the rate cut.

In the 7 cycles, before and after the first rate cut, US stocks (S&P 500 index) maintained an upward trend in all 4 "soft landings" and 1 "hard landing".

In terms of rhythm, US stocks usually adjust with fluctuations 1 month before and after the first rate cut, possibly because the market's judgment on the economic and policy outlook diverges.

However, unless there is a "hard landing", US stocks usually resume rising within 3 months after the first rate cut, with the S&P 500 index rising by an average of 2.8% compared to the day before the first rate cut.

In terms of style, the change in the style of US stocks before and after the rate cut is not obvious.

The reason may be that, on the one hand, the rate cut is beneficial to alleviate the valuation pressure of technology growth stocks, and on the other hand, it is also helpful to alleviate the financing and financial pressure of small and medium-sized and cyclical value companies.

Statistically, if it is not a market similar to the 2001 internet crisis, then the probability of technology growth stocks outperforming cyclical value stocks is relatively large; even during the internet crisis period, technology stocks also warmed up within 1 month after the Fed's first rate cut.

4.

Gold: Rise first, then consolidate The probability of gold rising before the rate cut is relatively large, but the trend after the rate cut is unclear.

From 2 months before the first rate cut to the day before the rate cut, the spot price of gold has risen 4 times, with an average increase of 1.8%; within 2 months after the first rate cut compared to the day before the rate cut, gold has risen 5 times; within 3 months after the first rate cut compared to the day before the rate cut, gold has fallen 5 times.

Moreover, there is no obvious correlation between the trend of gold and whether it is a "soft landing".

For example, in the "hard landing" of 2007 and the "soft landing" of 2019, gold rose significantly after the rate cut, benefiting from the safe-haven demand triggered by the subprime crisis and trade tensions, respectively.

However, in 1984 and 1989, the price of gold fell, mainly due to the decline in crude oil prices, inflation and inflation expectations.

5.

Crude oil: More likely to fall The probability of crude oil falling after the rate cut is relatively large, but not absolute.

In the 7 cycles, the price of WTI crude oil futures is more likely to rebound with fluctuations 1-2 months before the rate cut, and there have been 5 price increases from 2 months before the rate cut to the day before the rate cut, with a median increase of 2.8%.

After the first rate cut, the probability of crude oil prices falling is greater, with 5 declines from 3 months after the rate cut to the day before the rate cut, with an average and median decline of 6.0%.

The decline in oil prices may mainly be due to economic weakness and market concerns about demand.

04 Implications for the present Firstly, based on the economic performance before the Fed starts to cut rates, it is difficult to judge whether the US economy can smoothly "soft land" afterwards.

For example, before the rate cut in 1995, the ISM Manufacturing PMI declined rapidly and fell into contraction, and the growth rate of real private consumption also declined in stages, but after the rate cut, the US economy recovered rapidly, achieving a textbook "soft landing".

Another example is before the rate cut in 2007, the ISM Manufacturing PMI basically maintained expansion before the rate cut, and did not show a significant weakening trend, performing the best among the other 6 cycles, and the growth rate of private consumption was also at a medium level, but the US economy eventually fell into a severe crisis.

Interestingly, when the Fed cut rates in 2007, there were also concerns in the market about its premature rate cut triggering inflation to fluctuate repeatedly.

From this perspective, we need to fully realize the limitations of cognition in the market and policy, as well as the unpredictability of economic development.Secondly, if there are no severe economic or financial market shocks in the future, this round of interest rate cuts is more likely to achieve a "soft landing."

In fact, since the early 1980s when Volcker significantly raised interest rates to "create a recession," the United States has not experienced another recession directly caused by interest rate hikes alone without a severe economic or financial market shock.

The three "hard landings" since 1982 have been due to the savings and loan crisis (compounded by the oil crisis), the internet crisis, and the subprime mortgage crisis, respectively.

This has led to the Federal Reserve's interest rate cuts failing to prevent economic recessions.

In addition to these, the four "soft landings" have seen the Federal Reserve's appropriate interest rate cuts effectively preventing recessions.

Thirdly, the Federal Reserve began this round of interest rate cuts relatively late, with strong signals of a weakening economy and job market before the cuts.

This round of interest rate cuts by the Federal Reserve has been largely constrained by inflation risks, especially the rebound in inflation in the first quarter of 2024, which has significantly delayed the interest rate cuts.

Compared to the periods of 1984-1986, 1998, and 2019, the Federal Reserve has more compelling reasons for cutting interest rates, not only based on employment and inflation conditions but also to prevent the appreciation of the US dollar and to guard against imported economic and financial risks.

Compared to 1995, when US inflation was around 2%, the resistance to the Federal Reserve's interest rate cuts was relatively smaller.

This has also led to stronger signals of a weakening economy and job market before this round of interest rate cuts: first, the ISM manufacturing PMI is at a lower level compared to previous cycles (Chart 18); second, the pressure on the job market is significant, with the first occurrence of the "Sam Rule" being triggered before the interest rate cuts (Chart 21).

Fourthly, after this round of interest rate cuts, the economy and job market may also continue to decline for a period due to inertia.

Based on the economic performance after seven rounds of interest rate cuts, key production and consumption indicators, as well as job market indicators, are likely to continue to decline within a quarter after the first interest rate cut, and only bottom out and warm up in the second quarter after the cut.

Fifthly, the performance of major asset classes in previous interest rate cut cycles is expected to provide clues for the current asset trends, while also considering special macro backgrounds such as the US election and Japan's interest rate hikes for a comprehensive judgment.

Specifically:

Leave a Comment